By Luciano Martucci, independent anthropologist *

On August 20th, the holy week dedicated to San La Muerte, a folk saint not recognized by the Catholic Church but venerated mainly in certain regions of Argentina, Paraguay, parts of Brazil, and Uruguay, came to a close. In recent years, devotion to San La Muerte has transcended regional borders, spreading to other countries.Devotees invoke San La Muerte for protection, healing, and justice, especially in situations of great difficulty, such as illness, economic problems, legal issues, and matters of the heart. Depicted as a skeleton holding a scythe, San La Muerte bears similarities to the Mexican Santa Muerte but has distinct traditions and meanings. Like the new religious movement of Santa Muerte, this devotion is part of rapidly expanding new religious movements rooted in the syncretism between Catholicism and Indigenous beliefs, expressed through celebrations that include altars, prayers, and offerings.

The festivities for San La Muerte are celebrated from August 13th to 20th, with exact dates varying by city. However, he is also commemorated on Good Friday and All Souls’ Day, in homage to the clandestine practices during periods of obscurantism when the cult had to remain hidden, as well as the devotion practiced by those involved in illicit economic activities. Other commemorative dates include August 15, a day dedicated to the “Señor de la Humildad y la Paciencia” (Lord of Humility and Patience), also known as “Christ After the Scourging” or “Seated Christ.” This celebration coincides with the Feast of the Assumption of Mary, as some believe that San La Muerte accompanied her. On August 20, the anniversary of the saint’s apparition to an Indigenous person is celebrated. Traditionally, every August 20, homes with an altar dedicated to the saint are filled with devotees who come to thank him for favors received during the year or simply to express their presence.

During these festivities, many devotees celebrate San La Muerte in various locations in Argentina, and on the 16th and 20th of every month, they pay tribute to the saint with celebrations in which people participate enthusiastically and dance. Chamamé musicians and singers take turns ensuring that the vigil is never without music. Food is always abundant; all the necessary expenses for organizing the celebration and feeding the visitors are covered by the offerings, thanks to the generosity of the faithful who have donated throughout the year. On other occasions, some devotees, either to fulfill a promise or simply to please the saint and keep him content, bring food to offer to the faithful during the celebration.

At certain sanctuaries, such as the one called “Honor hacia mi Señor – El origen,” located in Villa Domenico, Wilde, a mass and baptisms were celebrated on August 17, but there are also testimonies of weddings being performed at some of the saint’s sanctuaries. This sanctuary officially received perpetual permission to conduct such ceremonies on August 14, thus achieving formal recognition as a sanctuary. During the celebration, a vigil with a mass is held, and tables and chairs are set up in the street for the faithful, along with a stage where various musical groups perform. To the rhythm of chamamé, couples prepare to dance, and most people have been participating in the festival for years, using the occasion to reunite and share experiences of faith, as well as to share food and socialize. The commemoration ends with a delicious BBQ, dancing, and a fireworks display.

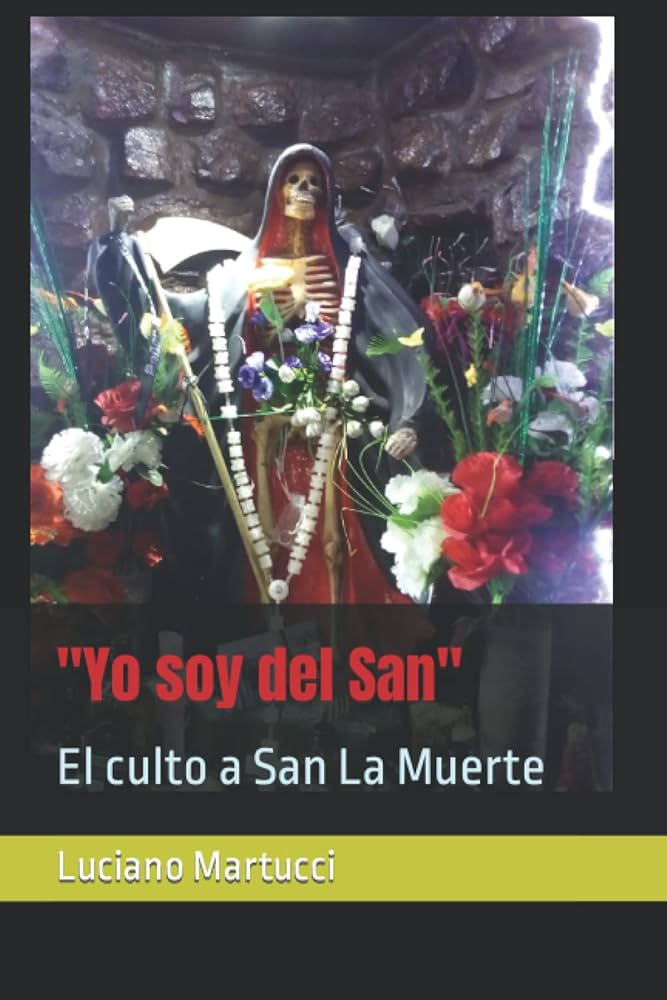

Some vigils begin at noon and continue until the following dawn. Throughout the week, the sanctuaries are continuously visited by devotees who bring offerings. There are also processions in honor of the saint that pass through the streets of the town or city where the festivities are held, accompanied by prayer leaders and weepers of San La Muerte. Hundreds, even thousands, of candles burn near the images of the saint. Floral decorations surround the small altars, adorning them. Traditionally, during the vigil, the weepers honor the saint with their laments while reciting prayers such as the Hail Mary or the Our Father, alternating them with popular prayers to obtain the miracles requested by the faithful.

In the Barrio Nuevo of Corrientes, the saint is celebrated on the 15th of every month. Here, Mrs. María Silvero and the servants of the Oratory of San La Muerte have been organizing the celebrations for over forty years. The traditional celebration starts early in the morning with the sharing of hot chocolate and sweets with the participants, who engage in prayers, requests, and mutual sharing of episodes of faith and life. They have lunch together, and then the celebrations continue with a small procession through the neighborhood streets. At sunset, a sort of chamamé festival takes place, with music and dancing.

The Santito de Alto de Monte Grande Chapel holds a service and celebrates the feast of San La Muerte. On the day of the celebration, the spaces fill with devotees who come to pay homage by bringing various types of offerings. The courtyard is filled with tables prepared for them, and they eat and dance together.

The sanctuary of Mrs. Pelusa Paniagua is located in Santa Inés, Posadas. When you arrive at the sanctuary, there are always people praying outside. The owner explains that the story of the saint has Guaraní origins and that her ancestors were Indigenous. She proudly states that they have been celebrating the saint for many years and that the Saint does not punish and is not evil; there is no need to fear him, only to respect him. Many people attend the celebration, bringing offerings. Some devotees, in gratitude for miracles granted, contribute with donations of drinks, wine, and liquor. Others offer meat, vegetables, and bread, which are cooked over a fire in a designated area outside the sanctuary and then served freely among devotees and curious onlookers. This year, over 500 kg of meat was offered to the approximately 1,500 visitors, accompanied by five musical groups, one of which came all the way from Brazil. Pelusa’s most significant message is that there are no special offerings for the saint; the most important gesture is giving a glass of water or food to those in need.

Among the most visited sanctuaries is the Sanctuary of Empredado, in Corrientes. It is said that the image of San La Muerte in the niche was found over a hundred years ago. The figure is a couple of hands high and appears to have been created using bas-relief techniques.

The Sanctuary of Solari, Mariano I. Loza, known as Estación Solari, Mercedes, Corrientes, welcomes hundreds of devotees each year who come from different places to celebrate the saint. At the entrance, visitors leave flags and banners with the image of the saint and other inscriptions as a memento and sign of their visit or in gratitude for miracles granted. A long white sign with black Gothic lettering reading “SANCTUARY OF SAN LA MUERTE” (where the “O” is a skull and the second “T” is a scythe) hangs above.

Inside, there is a fascinating niche containing a statue of the saint with a cloth tunic trimmed with gold lace and numerous gold chains. The saint is crowned with a splendid crown inscribed with “SAN LA MUERTE”; even the scythe, on the blade, bears numerous chains, giving the impression of being covered in a web of gold. Additionally, the sanctuary has various chapels or niches dedicated to the Saint and one to Gauchito Gil, a faithful devotee and servant of el Flaco. Next to this sanctuary is an enormous table, filled with bottles and glasses: anyone can help themselves, whether they couldn’t bring their own liquor from home or cannot afford to buy it. It is in front of this same niche that I will be taken after the statuette of the saint has been placed in my arms..

The holy week of San La Muerte is an event of great importance for the devotees, who gather to celebrate, pray, and share experiences of faith. These celebrations, although not legally recognized, represent a strong bond between the faithful and their spirituality, rooted in traditions that unite Catholicism with indigenous beliefs.

*Luciano Martucci, is a freelance anthropologist who focuses on shamanism, traditional medicine, and the religious diversity of Latin America. He has written several articles and published “Il Gauchito Gil, da bandito a santo”, “Il culto a San La MUerte” and “ Yo soy del San, el culto a San La Muerte.”